How people live without electricity

Blackouts in Ukraine

Nationwide blackouts began in October 2022. Before that date, electricity had almost never gone out in our area, except on rare occasions — not even during the period when we were “trapped” on all sides by the Russians. The only significant issue in spring 2022, as far as infrastructure was concerned, was the intermittent loss of internet connection. It happened sporadically, but nothing too serious, and usually the situation was resolved within a few days. The Russians had damaged some infrastructure along the Kyiv–Brovary route, causing disruptions to the network.

The blackouts, on the other hand, caught me — and Ukrainians in general — completely off guard. By the end of 2022, few people were prepared to cope with prolonged power outages. The Russian army kept targeting the country’s infrastructure not because it served any military purpose, but as part of their many acts of terrorism against the civilian population. They believed that, deprived of electricity and forced into inhumane living conditions, Ukrainians would either surrender or pressure their government into a ceasefire or a forced “peace.” Now, in September 2024, around 80% of Ukraine’s energy infrastructure is destroyed and nonfunctional. Restoring it to pre-war conditions will take years of repair work.

How do scheduled blackouts work?

The blackouts started off lightly, just a few hours a day, but as winter set in and temperatures dropped, they stretched on for nearly the whole day. Electricity use spiked as people tried to heat their homes during those few hours of power. Fortunately, at my in-laws’ house we had gas heating, which didn’t require electricity. What we did miss was water, since the electric pump wouldn’t work. For the internet connection, we quickly solved the problem by buying a small rechargeable battery for 20 euros. With one charge, it kept the modem running for 5–6 hours.

The power company, through Telegram (in Ukraine, hardly anyone uses WhatsApp), provided a chart with blackout schedules divided by district. Essentially, electricity in the region was distributed in shifts: in our area, we might get three hours of power in the morning and another three in the evening, alternating with the other districts (usually 4–5 in total). During the winter, that meant a total of about 6 hours of electricity per day.

The longest blackout we had that winter lasted about 48 hours. Without being able to use the computer or phone for such long stretches, I passed the time studying, reading books, or working out with a makeshift “home gym” in the living room. There wasn’t much else to do. Each time the power came back, we immediately charged all our devices, cooked meals, and washed up.

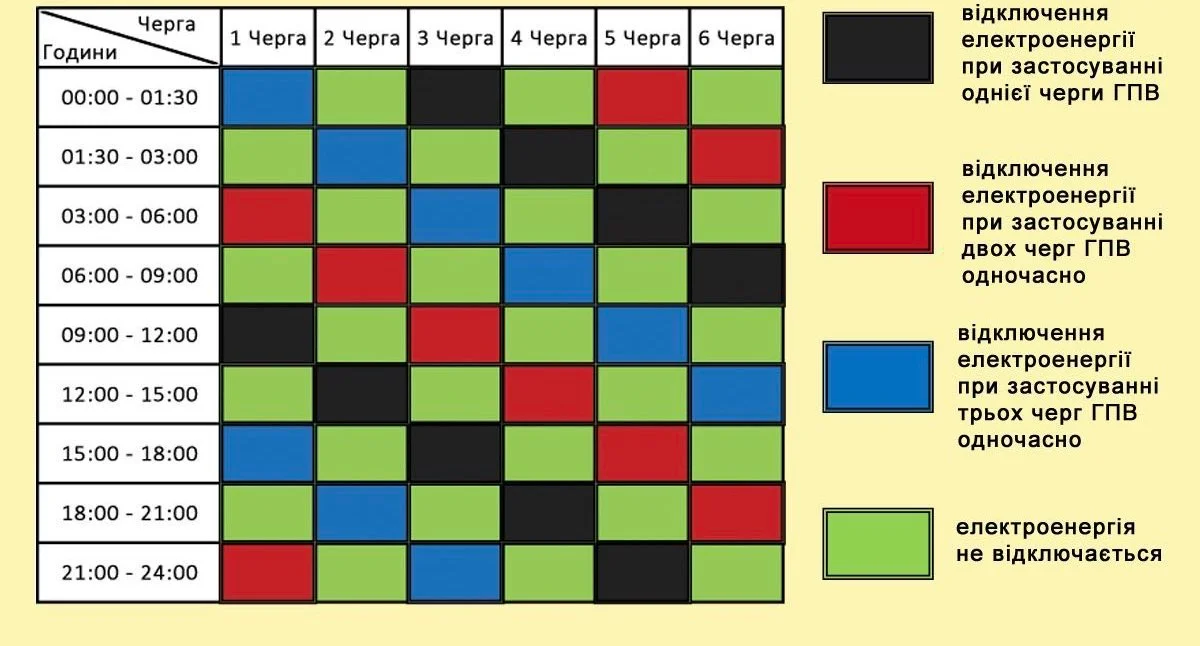

Below is the first chart showing the blackout schedules for the Chernihiv region. The numbers across the top row represent six districts, while the left column lists the hours of the day. Green blocks show the times when electricity was guaranteed in a specific district, blue and red blocks indicate when power might be cut depending on how many other districts were supplied at the same time, and black blocks represent complete outages. In July, some nuclear power plants were undergoing maintenance, and during that period they went offline. It was almost certain that during the red and blue time slots, the power would go out.

The second chart shows the situation in Kyiv, which was even more critical than in Chernihiv.

Methods to improve the situation

For the winter of 2023, we prepared by buying an Ecoflow portable power station, which ended up being useless, since there were no blackouts during that period. Unfortunately, this year Russia resumed its attacks on infrastructure, and already in the summer the situation became critical. In June and July, we were without electricity for about 12 hours a day. Now, with milder temperatures, the power supply has been stable again. For the coming winter, we prepared by buying a gasoline generator to use in emergencies, not 24/7, for two reasons. First, the economic factor: one tank lasts about 14–15 hours and costs 15 euros. Running it nonstop would cost at least 450 euros a month. Second, the noise: a gasoline generator averages around 60 dB, which would disturb the neighbors. During blackouts in Kyiv, nearly every shop runs a generator, and they become the constant “background music.” Whether you’re at the supermarket, in a metro station, or just walking down the street, the roar of the generators is always there to remind you of the war.

The coming winter

At the moment, as already mentioned, there are no particular problems thanks to the mild temperatures. However, the coming winter is expected to be colder and with even less electricity than in 2022. Many residential complexes—especially the newer ones in Kyiv—are organizing fundraising drives to buy generators so they can have light, water, and heating once the situation becomes critical. For example, in my apartment building—which we won’t return to until the war is over—they are asking for about 150 euros per household. It’s technically a “voluntary” payment, but not easy to coordinate, since many residents dislike paying the same amount as those with larger apartments, or a single person paying the same as a family of four. Even in these difficult times, tensions and misunderstandings among neighbors are common.

In conclusion, my family and I are as prepared as one can reasonably be for such a situation. However, many Ukrainian families will be forced to endure terrible months ahead, in the cold and under poor sanitary conditions. This is precisely why supporting Ukraine remains so essential.